The Pope and The Tsar, Metternich and Guizot

Franz Pokorny

The Soviet Union in the early 1980s presents a familiar scene. State and society rotten to the core, all statistics false. The country drags its feet in a just, but ultimately wasteful war on the imperial periphery. The thin coat of optimism; the brownite „sense of purpose“ that gilded the Stalin, Khrushchev, and even early Brezhnev years has chipped away, and only blunt repression — overseen by a general secretary parachuted in directly from the intelligence services — keeps the machine ticking. Suddenly, mystifyingly, the clouds part, and there is now a reformer clicking his heels and blowing cigarette ash on the Kremlin carpet. Space opens for dissent; it is now possible to openly criticise cancel culture and call out the insane Woke left. The new leadership in Moscow hints at renegotiating the terms of its arrangements with the empire’s satellite states. But is this really the thawing of the ice; the sudden, exhilarating rasputitsa that Ivan Ilyin considered the source of the Russian people’s volatile spiritual constitution, or merely the prelude to something else altogether?

There have long been whispers that glasnost and perestroika were but tentative first steps in a shadowy project of imperial rebalancing by deep state neoconservatives undergoing their own „posh turn“ towards market socialism and „traditional values“. The roots of this have been said to lie in the Soviet Union’s complex ecclesiastical politics; in a dialectic whereby the Orthodox Church, wholly infiltrated by the KGB and deployed during the great patriotic war to drum up support for the forces, had reciprocally imbued the security services with a warped, aestheticised version of its values. The result was a strange, apocalypticist byzanto-cameronism: a compassionate Soviet Union; strong on Defence. But something funny happened on the road from Gorbachev to Putin. Aided by local compradores plucked from the middleman minorities, „transnational civil society“ and organised crime launched an assault on the Soviet Union’s very foundations. An unholy alliance congealed between Maxwell and Mogilevich. Patriots were alive to the danger, but the generals’ putsch failed, and ethnic separatists seized the chance to tear the union asunder. Suddenly, Jeffrey Sachs was in the White House, and everything was for sale.

It would be unjust to President Trump to compare him to a damp squib like Gorbachev. Trump has singlehandedly, and for reasons entirely his own, forced history back open again. While the President’s bold course of reform has shooed the vultures from America’s prostrate body, the United States for the moment finds itself in the waiting room that the Soviet Union did in the 1980s: no longer on the death march on which Leonid Brandonzhnev was leading the country, nor yet in the clear. Like long-frozen vapours arising from a thawing bog, Trump’s awakening of America’s latent energies has released strange ideational compounds into the discursive air. Yet there is nothing new under the sun, and the veteran sovietologist observing the basic constellation of forces assembled to do battle in the swamp will have the feeling of having been here and seen it all before.

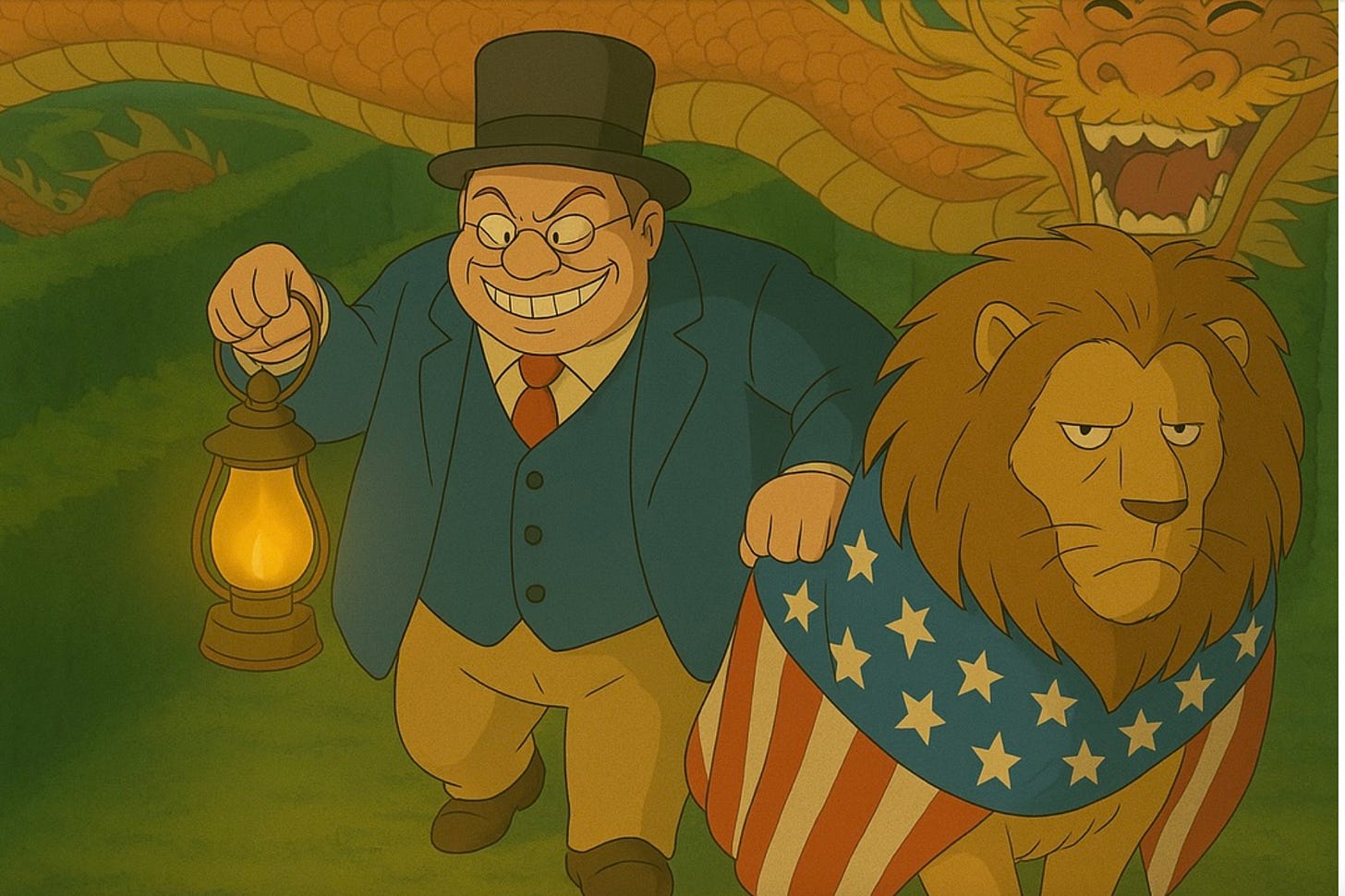

The battle over Trump’s foreign policy is in rough terms conducted between two camps. There are the patriotic hardliners — the junior KGB officers in Dresden — in the form of the Thielsphere and the more enlightened parts of the Pentagon. For all their eclectic intellectual predilections, these men pursue a simple project: a global War on Woke waged in the name of God, guns, and Girard. While their cause is distinct from that of Merit (which brooks no compromise on inheritance tax), they are nonetheless in broad alignment with the President’s visionary program. Then there are the reformers; the postliberals, who have their base in the Rubio State Department (whose policy planning staff contains no less than three former Budapest think tank sinecure holders). Like the late Soviet „liberals“, these men are rootless cosmopolitans; those strange dissidents more at home in the salons of Budapest, Tel Aviv, and Oxford than on the Arbat (Butterworth’s). Like Moscow liberals, they believe domestic reform intertwined in practical and ethical terms with a thoroughgoing reform of the international order, predicated on the unilateral relinquishment of their country’s vaguely immoral claim to global primacy. Multipolarism, tianxia — in these buzzwords we hear echoes of Gorby’s „Common European Home“, though the postliberals’ true sympathies are with something more akin to a sinophile version of the Kozyrev Doctrine. Among their Eastern European compadres there are a few liberals of the first hour (Viktor Orbán), and it somehow seems to have struck no one as suspect that they once again have Jeffrey Sachs in their entourage.

Not all the postliberals are unpatriotic, and the uninitiated in their ranks are fairly benign in their motivations („forgive them, President Trump, for they know not what they do“). However, living as they do in a mind prison of Paul Marshall’s making, their souls are rotted by a tortured pessimism vis-a-vis the trajectory of western culture, a mind virus which has corroded their psychological defences to the extent that a few decent performances by the Shanghai Philharmonic and decade-old essays about „reading Schmitt… in Beijing“ are sufficient to convince them of the Middle Kingdom’s katechontic significance. They are hostile to „our thing“, believing it to be philistery and decadence equivalent to Wokeness, with more than a hint of „Great Russian chauvinism“. While there is indeed much to admire, or at the very least respect, in China old and new, this variant of sinophilia is pathological: these are creaking senectiles who have given up on Youth, behaving in the marketplace of ideas as the boomers have in the housing market — building nothing new and bidding up the prices on old stock far beyond the underlying value.

The worst aspect of postliberal sinophilia is that not an ounce of it is original, but merely the latest tedious iteration of an incoherent despair in the face of eastern quantity and administrative skill that again and again throughout history rears its hideous norwooded head. Whether one accepts Galkovsky’s cryptocolony thesis or not, the idea of svengaling whatever the contemporary version of China happens to be to back one’s cause has been pursued by various factions within the West’s endless brothers wars since time immemorial. Both sides in the Corinthian War solicited Persian aid, and the preeminence that the Achaemenids enjoyed in Hellas in the aftermath of the peace brokered by Artaxerxes II might have continued indefinitely had not Isocrates heroically banged the drum of Brexit at the Macedonian court. The Italy of the Renaissance, as Burckhardt chronicles, was rife with schemers seeking a leg up from the ascendant oriental land power of the day, the Ottoman Turks, against their enemies on the peninsula. The dream of combining western „know-how“ with eastern economies of scale has seduced stouter chaps than George Osborne. Radley College Nanjing is a perennial archetype, present in the Indo-European mind before it had ever even heard of China.

Because the postliberals have accepted China’s ascendancy as a fait accompli, they are quite willing to defend policies that self-evidently harm America to the red communist dragon’s advantage, as long as doing so serves secondary goals like weakening Europe and Japan. The recent exchange between BAP and Oren Cass (who likes to play the China hawk) on Trump’s tariff policy is a case in point, and quite revealing as to the game the postliberals are playing. The crux of Cass’ argument is that BAP is wrong to say that China, plc. outcompetes America, GmbH. at the game of state capitalism; yet for America’s purportedly superior productivity to square with the undisputed fact of permanent Chinese export surplus, it must be the case that America and China exist in a kind of mercantilist arrangement; i.e. that economic activity is ordered not through the laws of supply and demand (or at leat not predominantly so), but through other institutional arrangements. So far, Cass has little disagreement with BAP, who has made precisely this point in reference to rare earths mining as an example of China-aligned actors abusing environmental regulations to destroy a competitive sector of the American economy. But whereas BAP wants to change such regulations or at least have them interpreted in such a way as to allow America to compete with China on stronger terms, Cass appears to tack to a maximalist institutionalism according to which the notion that „competition“ has any role to play in economic life is tantamount to market fundamentalism.