Epstein and the decline of Gossip

Notes

At age 10, I conceived of the only real ‘job’ appealing to me as ‘Prime Minister.’ At 14, I wanted to be James Joyce. At 17 I wanted to be Ludwig Wittgenstein and only at the mature age of 22 did I settle down and determine I really ought to found a new religion. I say all of this because I don’t quite know why I own a copy of the 50th anniversary A-Z of Private Eye and cannot remember who brought it for me but I want to dispel any impression J’accuse was the fulfilment of a childhood dream, or that I was the irritating sort of adolescent who is into Monty Python and ‘the satire boom.’

What is apparent from the book is that Private Eye’s Brezhnevian editor Ian Hislop is a far more sinister and ideological figure than appearances suggest. Many will know that he took over editorship of Private Eye at the age of 25, on personal recommendation of Richard Ingrams. What is less well known is that this was followed by a purge of personnel in which Hislop’s own loyalists were installed and that this contributed to an objective transformation in the paper’s ideological standpoint.

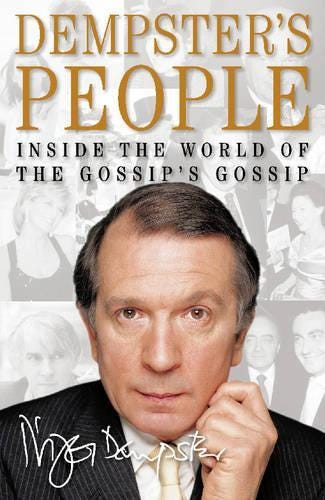

The main opposing party in this confrontation was Private Eye’s diarist Nigel Dempster who wrote the Grovel column (Private Eye maintains several named columns like ‘Books and Bookmen’ for publishing, ‘Street of Shame’ for the goings on of journalists etc.) A very quick perusal of Dempster’s Wikipedia page and obituary will give you all you really need to know about him: a genuine British eccentric of the old Fleet Street who would be universally dismissed today as an “awful little man” by people who attempt to mimic the aesthetics.

Brexit trade deals

The cause of the dispute, wherein Dempster advised Hislop against printing a story on disgraced Tory minister Cecil Parkinson, which Hislop did anyway and was duly subjugated to a “doesn’t suffer fools gladly” telling off, is less interesting than Hislop’s agenda. I shall quote Hislop on his motives:

“I hated Grovel, admits Ian Hislop. I couldn’t see the point of it. It wasn’t funny, never even entertaining… It is not that I’m asexual, or celibate or anything dramatic like that, but just endlessly reading about it was something I felt we could leave to Murdoch, really.”

Hislop eventually shut down the ‘Grovel’ column permanently after starting another feud with Dempster’s successor, Christopher Silvester. This is plainly an ideological, rather than commercial, choice. Hislop had made, on the grounds of his purely religious moral views, a decision that Dempster’s form of journalism – which had netted the Eye many good stories (like exposing the musician Jonathan King as an abuser of teenage boys 20 years before the courts) – was ‘not real journalism’ because it was immoral to produce and publish. Hislop believed this because he was an Anglican Christian. It was, in other words, a calculated attempt to make Private Eye more subservient to power.

I couldn’t help thinking about this basically irrelevant piece of journalistic trivia watching the continued mock-disbelief surrounding the Epstein scandal. If you wanted to expose Jeffrey Epstein in 2004, someone like Nigel Dempster, a man who abused and successfully upgraded his aristocratic credentials to spy on the elites; and who could not be blackmailed because he made it clear, by his public manner, that he was amoral, would’ve been far more game for the job than Ian Hislop. The things Hislop accuses Dempster of: being obsessed with royalty, fostering aristocratic connections, prioritising primary source-gathering over ‘investigative journalism’ are all the things that ultimately would’ve revealed the Epstein scandal sooner.

Imagine a Dempster upgraded for the 2000s with an expenses account to accommodate the jet set life. Imagine a man who, in all likelihood, knew Ghislaine Maxwell at university; who had the credentials to meet Prince Andrew in casual settings and who wasn’t going to be intimidated by a Hampstead Gardener like Peter Mandelson threatening to “tell your editor.” Such a person would’ve sniffed out the Epstein scandal in 2004 and saved the lives of countless victims as well as huge amounts of British taxpayer’s money and national honour.

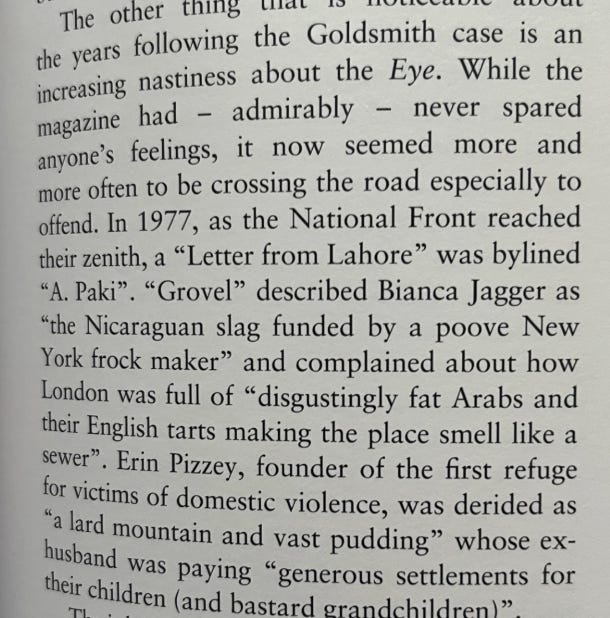

One of the compliments I most resent in life is ‘you should be editing Private Eye’: I am a political philosopher, a blockchain entrepreneur and the most influential young British politician of the decade, thank you very much and if anyone deserves that job, it is The Laughing Man. However, despite the corniness of the present day magazine, it is worth getting some context on what Private Eye used to be in the 1970s before Hislop. The Israeli newspaper Haaretz described Private Eye as “an obscure magazine combining antisemitism with Trotskyism”; in this period, it united left-wing Republicans with right-wingers like Christopher Booker (an early Brexiteer) on a platform of opposition to the Monarchy, Maxwell and Harold Wilson. It is noteworthy that the sainted Peter Cook would record himself going on hours-long anti-Semitic rants while off his head on ecstasy. The same book also contains apologetic entries on the magazine’s lampooning of homosexuals (which included outing Peter Mandelson in 1987).

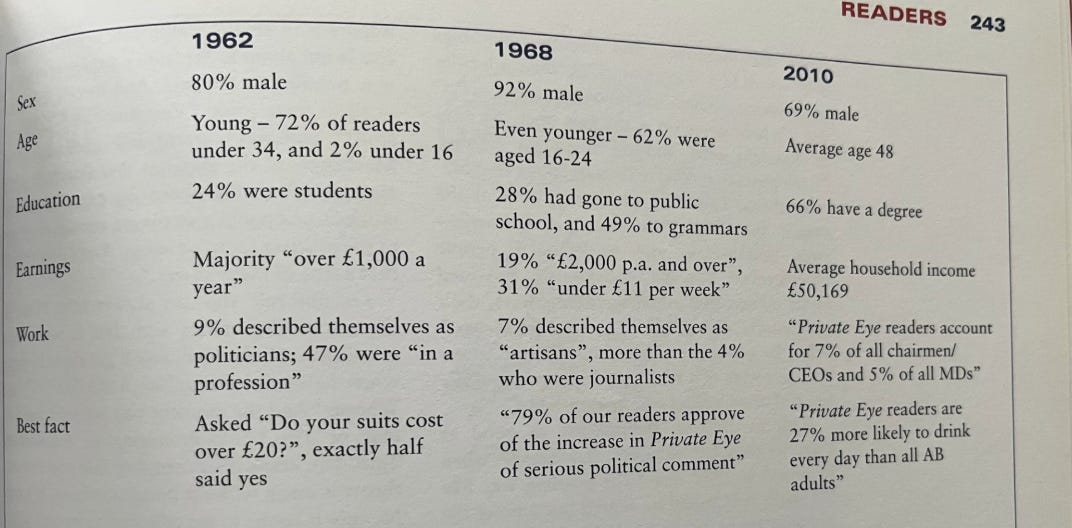

Survey of reader demographics.

Gossip, far from being an alien import to Private Eye from the Murdoch press, was in fact the stock-in-trade of the publication and what made it genuinely hated by “the Establishment.” All of Private Eye’s greatest scoops and famous writs arose from unsubstantiated rumours collected from the circle of acquaintances common to the public school founders. Throughout the book, Hislop proudly claims he “cleaned up” the magazine, removing the public school racism and also the sex ads which used to litter the back pages, on becoming editor, he states one of his goals as reducing the number of court cases: which meant less personal harassment of rich and famous people.

Hislop generally redirected the paper towards ‘investigative journalism’ which, it is true, has revealed some genuinely interesting stuff (like the dodgy dealing of levelling-up champion Ben Houchen) but it is etiolated by the media persona Hislop has adopted as the moral conscience of journalism. Within this worldview, it is assumed that politicians are “crooks” and hacks “bent” but the purpose of writing is not to agitate for their removal by revolutionary action, or personally insult them but expose their “hypocrisy” to a democratic public sphere consisting of other ex-public schoolboys. Within this worldview all “hypocrisy” is equal but while this might be emotionally gratifying, it isn’t morally or logically consistent. If New Labour allowed a man who was friends with a convicted human trafficker to sell state secrets for sex and money, then this does in fact entail that Nigel Farage fiddling with his expenses is not a big deal, if Nigel Farage is the only person willing to prevent graver offences (this is, at present, dubious).

The Hislop era coincided with a great transformation in public attitude to celebrities, beginning in the 2000s and achieving total victory by the late 2010s, in which ‘the Epstein aesthetic’ emerged. People like footballers, reality T.V stars and especially the British Monarchy were increasingly being treated as serious individuals. It was, ironically, Dempster’s style of journalism which would expose the biggest stories of this age and which had the biggest following among young people. TMZ, 8chan and Wikileaks are all essentially gossip journals. The narrative that people like Dempster were boozy old fossils is incorrect, they were the wave of the future.